Settlement History

Shark Bay was first settled by Europeans in the 1850s and was important for industries such as guano mining, pearling and pastoralism.

Guano mining was the first land-based industry in Shark Bay and initiated European settlement of the area in 1850. It also provided the colony of Western Australia with one of its earliest commercial exports.

Guano was valuable and in demand before development of chemical fertilisers. A Peruvian monopoly on guano made it prohibitively expensive so its discovery in Shark Bay was well received in Australia and Europe.

Mining started in 1850 at Egg Island off the east coast of Dirk Hartog Island then progressed to, and quickly stripped, at least 13 islands in Henri Freycinet Harbour. These included Smith, Sunday and Eagle islands, and North and South Guano islands.

Anxious to protect this valuable commodity, the Government established a garrison at Quoin Bluff on Dirk Hartog Island in 1850. Another military outpost was later established at Cape Heirisson.

Guano was valuable but the stakes were high. Bad weather, uncharted shoals and unsure anchorages made it difficult for large vessels. In 1850 the 443-ton barque Prince Charlie struck the Levillain shoal off Cape Levillain after loading guano. This shoal also claimed the 125-ton barque Macquarie with guano cargo in 1878. The shipwrecked sailors struggled back to Cape Levillain then walked south for three days without food or water until rescued by a vessel in South Passage.

The Shark Bay pearl oyster, Pinctada albina, spawned a rush not unlike the gold rushes of the 1800s. Sought after were small straw-coloured ‘seed’ pearls favoured in Asian markets, and pearl shell used to make buttons in the days before plastic fasteners. Pearling began in the 1850s and peaked in the 1870s leaving reminders of the industry all around Shark Bay.

Commercial harvesting began after a government official investigating the guano industry saw potential in Shark Bay’s prolific oyster banks. At low tide shell could be picked by hand or collected by divers, but dredging was the most efficient harvesting technique. This involved dragging wire-meshed baskets over oyster banks behind a shallow-draught, single-mast sailing boat. About 80 boats were working the banks of Shark Bay by 1873.

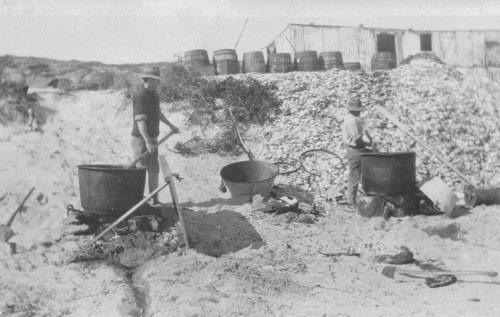

Men collected oysters while women and children cleaned the shells and put the inedible oyster flesh into barrels called ‘pogey pots’. The flesh was left to rot in the sun then boiled until any pearls dropped to the bottom of the pot for collection. The odour was sickening and could be smelled for miles around. There might be just two or three pearls in every hundred shells opened.

The pearl shell was sorted and the best sent to England, France and Germany. Lesser-grade shell was discarded or put to novel use.

The town of Denham was once a large pearlers’ camp called Freshwater Camp and its streets were paved with iridescent mother-of-pearl.

In the rush for riches many European entrepreneurs forced Aboriginal people to labour alongside indentured Chinese, Pacific Islander and ‘Malay’ workers. Treated like slaves the workers suffered terribly and those promised wages did not always receive them. Some Chinese pearlers brought their own vessels and operated in direct competition with the Europeans, causing resentment and conflict.

Some men drowned while diving or when boats sank, and two were killed in a cyclone. Camps were mainly tents and corrugated iron huts harbouring dysentery and other diseases. Many pearlers are buried on the sand dunes behind the beach at Willyah Mia.

The industry ended as once-prolific banks were stripped bare and plastic buttons were introduced in the 1920s and 30s. Many old pearling cutters were then pressed into service as fishing boats as they were useful for net fishing in shallow water.

The wild pearl oyster is now recovering on the banks scraped by the dredges so many years ago while cultured pearls are commercially cultivated in Red Cliff Bay near Monkey Mia.

Pastoralism was one of Shark Bay’s earliest and longest-running industries with the dry climate well-suited to sheep. The first pastoral leases were granted in the 1860s and more than 15 sheep stations were established across Shark Bay. The first was built on Dirk Hartog Island in 1869 and by the 1920s the island’s flock numbered 26,000.

Progress on some stations was hampered by the difficulty of getting wool to the market. There were few roads so wool bales were taken by camel or horse-drawn carts to a dinghy to be ferried to a larger boat. Loading was done from the south coast of Henri Freycinet Harbour and at Flagpole Landing.

Lack of fresh water was also a problem. In coastal areas brackish water was initially pumped from shallow beach wells into tanks and troughs for sheep to drink. More than 100 artesian bores were later sunk throughout the region. About 150 km of pipeline carried water from bores on Peron Station alone.

In the early 1950s wool was worth a fortune and Hamelin Station took 776 bales of wool from 26,600 sheep in one year. By the 1960s there were about 142,000 sheep in Shark Bay.

However, times were not always good. A drought in the mid-1930s saw the Carbla Station flock on the eastern shore of Hamelin Pool plummet from 24,000 to 10,500. Another drought late in the 1970s reduced Shark Bay’s flocks to an all-time low.

The collapse of the wool market in the 1990s forced stations to further reduce their flocks and look for alternative income. Sheep were replaced with cattle at Carrarang and Tamala while Hamelin Station took on goats. Dirk Hartog Island and Nanga combined pastoralism with tourism operations.

The first shipments of sandalwood, Santalum spicatum, left Shark Bay in the 1890s. Pastoralists commonly cut the aromatic timber to supplement their income. Sandalwood was harvested for more than 100 years, mainly for export to south-east Asia, before licences were phased out in 2000.

Loading the timber for export was hard work as the parasitic sandalwood’s favoured host, ‘dead finish’, has large thorns and harvesters had to cart the sandalwood through spiky thickets to the nearest beach. From the beach sandalwood was taken by small craft to a waiting ship.

A 16-ton cutter, Two Sons, sank with a cargo of sandalwood on its way from Flint Cliff to Denham in 1902.

Fishing has been Shark Bay’s economic mainstay since the early twentieth century. It is a major source of employment and notable for the long-time involvement of Aboriginal people whose knowledge and skill have helped preserve traditional fishing methods and fish stocks.

Shark Bay supports Western Australia’s major fisheries for prawns, scallops, snapper and western sand whiting. But it was not until the early 1930s when the first freezers were built that the industry was really established. Before then Shark Bay was too remote for the industry to be viable.

In the 1930s when commercial fishing became an alternative to the fading pearling industry, Shark Bay fishers used their shallow-draught pearling cutters to net fish the Bay’s shallows and flats. The beach seining fishing technique used by local Aboriginal people incorporated a wealth of knowledge gathered over thousands of years and is still used today.

A boat towing one or two dinghies anchors in the fishing area and some crew take the dinghies while another goes ashore to a good vantage point to look for fins, surface ripples or other tell-tale signs of schooling fish. Experienced fishers can identify different species and the average size and weight of individual fish in a school. A school of snapper appears blue-black in the water, whiting looks brown, sea mullet looks silver, and bream have golden flashes.

Once fish are sighted, a crew member jumps from a dinghy with one end of the net while the dinghies run the rest of the net around the school. Both ends of the net are then taken to the beach, working the trapped fish into the shallows.

Shark Bay’s beach seine fishery targets mainly sand whiting, although bream, sea mullet, tailor and snapper are also prized catches. This is a limited entry fishery – fishing licenses cannot be sold or exchanged, only handed down within Shark Bay families. This ensures the traditional fishery is maintained and that fishers are careful to conserve fish stocks.

Larger vessels operating mostly out of Carnarvon catch a variety of other species. They too operate under strict conditions which include restrictions on boat size, catch size, fishing gear and must have turtle exclusion devices in prawn nets. The main catches are:

- Prawns, particularly brown tiger prawns (Penaeus esculentus) and western king prawns (Penaeus latisulcatus). Prawns have been fished in the region since 1962, with much of the catch exported to Japan, Taiwan, Europe and the USA.

- Saucer scallops (Amusium balloti) have been fished since the late 1970s with meat usually sold to Asian markets.

- Pink snapper (Pagrus auratus) is a relatively long-lived species that has been over-fished in the past and is now subject to strict bag limits. It is primarily exported as whole fish to Japan, Taiwan, Italy and the USA.

- Blue swimmer crab (Portunus pelagicus), a relatively new commercial harvest, is caught in Shark Bay’s northern waters. The crabs represent about 45% of the total catch in Western Australia and are mostly exported.

Other commercial operators provide charter boat tours for recreational fishing. Like commercial fishers, recreational fishers must adhere to rules developed to suit Shark Bay’s ecology, species mix and fishing pressure.

Hamelin Pool Telegraph Station includes the post office and postmaster’s quarters and is testimony to the first telecommunications in Shark Bay. Built in 1884 this telegraph station is one of the few surviving relics from a chain of stations that stretched from Wyndham to Albany. The buildings are listed on Western Australia’s State Register of Heritage Places.

This repeater station on the coastal line between Geraldton and Roebourne was originally called Flint Cliff Telegraph Station due to its proximity to a cliff used as a landmark by supply vessels. The line itself was a single strand of wire suspended on porcelain insulators on top of a series of rough wooden poles. Some of the original poles can still be seen along Shark Bay’s northeast coast.

Messages were sent by signals tapped in Morse code. These pulses of electricity flowed along the line to telegraph stations where banks of large batteries provided the necessary voltage to send the message on to the next station.

The system revolutionised communications but had its problems. Strong winds often blew branches across the wire, and poles were struck by lightning or washed away in floods. For many years full-time linesmen rode along the line, first on camels and later in trucks, inspecting the line and making repairs.

Later the post office also acted as the telephone exchange, but the arrival of coaxial cable in the 1970s made Hamelin Pool Telegraph Station obsolete. By the 1990s satellite technology revolutionised communications once again.

Hamelin Pool Telegraph Station is now a privately-owned enterprise. The original post office has been converted into a museum full of telegraphy paraphernalia and also houses a living stromatolite. Close by you can see where shell blocks (coquina) were quarried to build station homesteads and some of Denham’s oldest buildings.

Today Shark Bay is a popular destination for nature-based recreation. It began with fishing and the Monkey Mia dolphin experience, which both remain popular alongside a growing demand for other Shark Bay experiences.

Popular activities include fishing, camping, four-wheel driving, birdwatching, snorkelling, diving, boating, kayaking and photography.

Careful environmental management is vital for the protection and maintenance of Shark Bay’s World Heritage values and some areas previously used for pastoralism have been purchased for conservation.

Since 1990 pastoral lands have been purchased for conservation:

- Peron, a 40,000 hectare station grazed since 1881, was bought by the Western Australian Government in 1990 and gazetted as Francois Peron National Park in 1992. Feral animal control programs under Project Eden have resulted in rejuvenation of degraded ecosystems and the reintroduction of threatened species into the park.

- In 1999 the Australian Wildlife Conservancy purchased Faure Island, embarking on a successful program to eradicate sheep and goats then introduce native species.

- Nanga Station was bought by the Commonwealth and Western Australian Governments in December 2000 to better conserve Shark Bay’s World Heritage values, including its tree heath.

- Part of Tamala Station is proposed as a nature reserve, to better protect the spectacular Zuytdorp Cliffs. Tamala also features historic water tanks, wells and stock fences.

- Most of Dirk Hartog Island was declared a national park in 2009 and an ecological restoration project is eradicating feral animals in preparation for restoring native species to the island.

- Bush Heritage purchased Hamelin Station in 2015 for conservation purposes.