Maritime History

Dirk Hartog’s landing in 1616 was the first recorded landing of Europeans in Western Australia and marked the beginning of a series of expeditions revealing Terra Australis Incognita, the unknown south land.

Studies and collections made by explorers of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries represent some of the earliest scientific records of Australia’s people, landscape, flora and fauna.

Dirk Hartog was a Dutch seaman born in 1580. He spent his early career trading as a private merchant in the Baltic and Mediterranean seas before joining the Dutch East India Company (VOC) as a steersman. In 1615 he was appointed master of the VOC ship Eendracht and in January 1616 set sail with a fleet of VOC ships for Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia) to trade in spices and other goods.

Eendracht was separated from the fleet during a storm before the Cape of Good Hope but continued sailing about 7,000 km east before turning north and setting a course for Batavia. But Hartog sailed further east than he should have and made the first recorded landing of a European in Western Australia on 25 October 1616 when he dropped anchor off what is now known as Dirk Hartog Island.

To record his visit for posterity Hartog climbed a cliff, now called Cape Inscription, and set a wooden post in a cleft of rock. He nailed to the post a pewter plate inscribed with a brief account of his visit.

Hartog’s plate remained on the cliff for 81 years until rediscovered in 1697 by another VOC captain, Willem de Vlamingh. The oldest known physical record from Australia’s European history, the plate is now preserved in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Cape Inscription area is included in Australia’s National Heritage List as a place of national significance.

Hartog continued north charting along the way, and his name for the region – Landt van d’Eendracht, or Eendracht’s Land – began appearing on world maps.

Dutchman Willem de Vlamingh was born in 1640. When aged just 24 took command of his first ship and for several years hunted whales and walruses off Greenland and northern Russia.

In 1688 de Vlamingh joined the VOC and made his first voyage to Batavia in the same year. Following a second voyage in 1694 he was given command of three vessels – Geelvinck, Nijptangh and Het Weseltje – to search for Ridderschap van Holland, a VOC ship lost en route to Batavia. De Vlamingh was also to chart the southwest coast of New Holland to improve navigation for merchant shipping.

The three ships set sail from Amsterdam on 3 May 1696. Although they did not find the Ridderschap van Holland, de Vlamingh did chart parts of Western Australia’s coastline and explored Rottnest Island and the Swan River before anchoring in South Passage off the southern tip of Dirk Hartog Island 30 January 1697. Several days were spent exploring the area and collecting turtle eggs on a beach now known as Turtle Bay.

They found Dirk Hartog’s plate at Cape Inscription on 4 February 1697. Recognising its historic value, de Vlamingh removed the plate and replaced it with his own. Onto the new plate was copied the original inscription and added an account of his own landing. He returned Hartog’s plate to Amsterdam.

On 11 February 1697, de Vlamingh’s fleet set sail for Batavia. His plate remained untouched at Cape Inscription for 104 years before being found by Nicolas Baudin’s expedition in 1801.

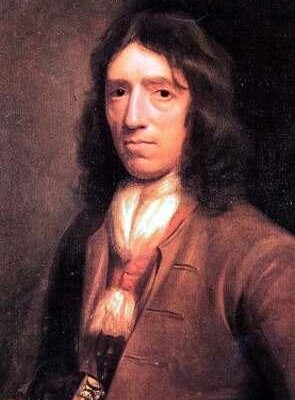

William Dampier was an English navigator, explorer, privateer and writer who lived from 1651 to 1715. He had numerous adventures around Central and South America and the Pacific, and in 1688 spent a short time in northwest Australia. Dampier’s careful charts, illustrations and account of his travels published in A New Voyage Around the World aroused the interest of the Royal Society and the Royal Navy. In 1697 Dampier was commissioned to explore the coasts of New Holland aboard HMS Roebuck.

He arrived at Dirk Hartog Island in August 1699 and anchored at a place now called Dampier’s Landing and did not see the inscribed plate left by Willem de Vlamingh just two years earlier. Dampier explored the island and surrounding waters and noted Bernier and Dorre islands and the northern tip of Peron Peninsula, which he thought was an island. During this time Dampier’s cook, Mr Goodwin, died and became the first European known to have been buried on Australian soil.

Dampier made many detailed observations of local wildlife and named the area ‘Sharks Bay’ in recognition of the large number of sharks in the area. He also made the first scientific collection of Australian plants. His collection is still preserved at the Oxford University and includes Dampiera, a blue-flowering genus that now bears his name.

After a week in Shark Bay the Roebuck sailed north to the Dampier Archipelago, Roebuck Bay, Timor and beyond. Dampier had planned to explore the east coast of Australia, but the Roebuck leaked so badly he was forced to return to England. The ship sank at Ascension Island in the Atlantic Ocean but Dampier and crew were rescued just over a month later.

François de Saint-Alouarn was a French navigator who accompanied Yves-Joseph de Kerguelen-Tremarec in a search for the mysterious ‘Gonneville Land’, a continent supposedly situated in the southern seas. They left Ile de France (Mauritius) in 1771 with the Fortune captained by Kerguelen and the Gros Ventre captained by Saint Alouarn.

In February 1772 Kerguelen sighted land but after the ships were separated by a storm he returned to Ile de France convinced he had discovered a continent. It was in fact a sub-Antarctic island now called Kerguelen Island. Saint-Alouarn abandoned his search for the Fortune and sailed on, reaching Cape Leeuwin in Western Australia in March 1772.

On 30 March 1772, Saint-Alouarn landed at Turtle Bay on the northern tip of Dirk Hartog Island. There he claimed possession of the western half of New Holland for King Louis XVI. This was two years after Captain James Cook landed at Botany Bay, and 16 years before the arrival of the First Fleet. To support the claim he buried two bottles containing statements of proclamation written on parchment. Two silver coins were placed on the top of each bottle, which were sealed by lead caps. The coins, lead seals and one of the bottles were discovered by archaeologists in 1998 and are now on display in the Western Australian Maritime Museum.

Saint-Alouarn did some survey work and lost two anchors north of Peron Peninsula before continuing north to Timor and west to Ile de France. His claim on the continent was never enacted and he died in Ile de France in September 1772 aged just 35 years.

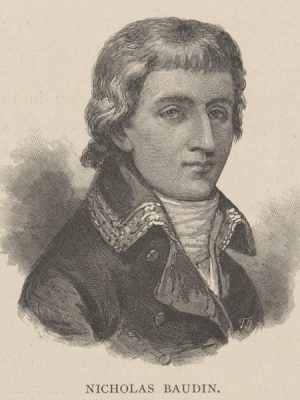

Thomas Nicolas Baudin was born in 1754 and joined the French Navy in 1774. Under orders from Napoleon Bonaparte he led a voyage of discovery between 1801 and 1803 that contributed significantly to knowledge of Shark Bay and much of Australia.

In 1801 Baudin’s corvettes, Le Géographe and Le Naturaliste, spent 70 days in Shark Bay with the ships’ companies exploring, mapping and naming many features. They named Bernier Island for the expedition’s astronomer, Bellefin Prong for Le Naturaliste’s surgeon and Heirisson Prong for Le Naturaliste’s sub-lieutenant. The navigator-surveyor Louis de Freycinet named Henri Freycinet Harbour for his brother and Cape Lesueur for Le Géographe’s artist. The expedition’s naturalist, François Péron, explored the peninsula that now bears his name.

During a trip to Dirk Hartog Island the commander of Le Naturaliste, Emmanuel Hamelin, discovered the plate left by Willem de Vlamingh in 1697. Believing it sacrilegious to remove the plate, Hamelin instead nailed a lead plate recording his own visit to another post on the northeast side of the island. Hamelin’s post and plate have never been found.

After surveying Tasmania and Australia’s entire southern coast the expedition returned to Shark Bay in March 1803. Landing parties from Le Géographe made excursions to different parts of Peron Peninsula, which Péron crossed from east to west making notes on fauna, flora and the Aboriginal people. These were the first written descriptions of the Malgana people to be presented to the outside world.

Baudin died of tuberculosis in Ile de France (Mauritius) in 1803.

Francois Peron was born in France in 1775 and while travelling as a naturalist on Baudin’s expedition was among the parties exploring Shark Bay in 1801. In doing so he made some of the earliest recordings of Shark Bay’s wildlife and first people. It is in his honour that Francois Peron National Park is named.

The eldest son of a poor village family, he contracted smallpox when four years old and this left him blind in one eye. After studying in a monastery he became a soldier in the Napoleonic wars and was severely wounded and taken prisoner.

In 1800 Peron achieved a position as pupil zoologist on the Baudin expedition. They first arrived in Shark Bay in July 1801 and undertook extensive surveys involving collection of many specimens.

During the return voyage in 1803, the Geographe anchored offshore from Cape Lesueur on 19 March. On hearing reports of Aborigines on the mainland Peron organized a walking expedition across the peninsula from west to east. He was accompanied by Petit, an artist, and Guichenault, a gardener. They attempted to communicate with some Aborigines near Herald Bight, but the Aborigines fled.

Peron’s focus on scientific exploration throughout the three year expedition “impelled by my zeal, and the pleasure I had in the important discoveries I was making” often led him to disregard Baudin’s orders and contributed to ongoing friction between the two men during the expedition. Peron was also in the habit of getting lost and returning dehydrated and exhausted while exploring.

These habits were a constant source of irritation to Baudin and he wrote in his journal after the peninsula crossing: “This is the third escapade of this nature that our learned naturalist has been on, but it will be his last, for he shall not go ashore again unless I myself am in the same boat.”

Peron was the leading scientist on the expedition when the Geographe returned to France in 1804. Of the 23 scientists who began the expedition, only three returned. Peron was the only zoologist to complete the trip and to him fell the task of writing the zoological results. His work was illustrated by Charles Lesueur who had joined the expedition as a gunner.

Many of the 100,000 animal specimens taken to France on the Geographe had been collected in Shark Bay and Peron’s writing established him as the father of anthropology. The specimens represented almost 4,000 species – one of the greatest achievements in scientific history. Of these, more than 2,500 were new to science. While he became famous amongst scientists in France, he was not recognized elsewhere.

Péron died of tuberculosis in 1810, six years after returning to France. Many of the expedition’s manuscripts were finished by Louis de Freycinet.

Louis Claude de Saulces de Freycinet was born in 1779, joined the French Navy in 1793 and was a veteran of Baudin’s voyage of discovery from 1801 to 1803. In 1817 he was given command of the corvette L’Uranie with the commission to finish some of the surveys and scientific work left incomplete by Baudin. This included studies of natural history, anthropology, geography and magnetic and meteorological phenomena. His wife Rose refused to be separated from her husband and joined the ship’s company as a stowaway.

L’Uranie sailed into Shark Bay in September 1818. De Freycinet set up an astronomical observatory near Cape Lesueur and spent some days collecting botanical specimens and exploring the inlets and coastal areas. His company also met with a group of Malgana people, a tense encounter that was diffused with dancing and an exchange of gifts.

A party was sent across to Dirk Hartog Island to recover de Vlamingh’s plate, which de Freycinet had first seen in 1801 during Baudin’s expedition. Back then de Freycinet had disagreed with his commander’s decision to leave the plate on the island. He believed “its natural place to be in one of those great scholarly and scientific storehouses which provide historians with such rich and precious documents”. Under his own command, the plate was eventually delivered to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Elegant Literature in Paris. There it stayed until 1947 when the French Government presented it to the people of Australia. The plate is now in the Western Australian Maritime Museum.

After briefly running aground on a sand bank between Bernier and Dorre Islands and the mainland, L’Uranie headed north to Timor, through the Pacific, south to Sydney and around Cape Horn. Her luck ran out in February 1819 when she was wrecked off the Falkland Islands. More than half of the scientific specimens were lost but the entire ship’s company was rescued by a whaler which de Freycinet purchased, renamed La Physicienne, and sailed back to France.

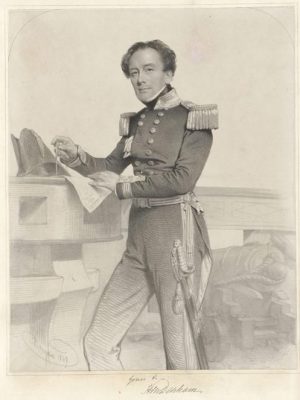

The town of Denham is named in honour of Captain Henry Mangles Denham who spent three months charting Shark Bay in 1858. Denham’s hydrographical survey was conducted partly in an effort to find alternative locations for convict settlements and was the longest running survey ever commissioned by the Royal Navy. The project ran from 1852 to 1861 and produced charts so accurate they were still being used in the 1960s.

Denham’s survey work was conducted from HMS Herald, a square-rigged wooden frigate. Landings were made at numerous locations, including Little Lagoon, Cape Lesueur, Hamelin Pool and Herald Bight. At Quoin Bluff on Dirk Hartog Island, Denham found the remnants of the garrison established in 1850 to protect the guano trade.

He managed to navigate the shallow waters of both the eastern and western gulfs and named several islands including Pelican, Smith, Wilds and Egg islands. Salutation Island was so named after a friendly encounter with Aboriginal people who were invited on board the Herald and given gifts. But the names Hopeless Reach, Disappointment Loop and Disappointment Reach suggest Denham’s work was also full of frustrations.

Denham’s survey is remembered with the Denham Channel leading to Shark Bay and Denham Sound which provides anchorage for large vessels. Denham also quite literally put his name on the landscape at Eagle Bluff where the words “HERALD DENHAM 1858” were carved into the limestone cliff. When this section of rock broke away from the cliff it was moved to the township, and is now on display in Denham’s Pioneer Park.