Plants of Shark Bay

Located at the transition of two botanical provinces, Shark Bay has more than 820 plant species. This includes 53 species endemic to Shark Bay, many rare and threatened species and others at the limit of their geographic range.

In Shark Bay plants found in temperate southwestern Australian woodlands mingle with desert plants – Acacia, samphire and spinifex scrublands.

Shark Bay’s vegetation features plants of both the arid and temperate botanical provinces.

The South West Botanical Province is dominated by plants typical of cooler, wetter south-western Australia. These include members of the Proteaceae and Myrtaceae families and are common on the southern part of Nanga Peninsula, the eastern part of Tamala pastoral lease, and the Zuytdorp Nature Reserve.

The Eremaean botanical province is dominated by desert-adapted species such as Acacia, samphire and spinifex. Vegetation on Peron Peninsula is mainly Eremaean. Monkey Mia, for example, is heavily populated by limestone wattle (Acacia sclerosperma), bowgada (Acacia ramulosa), kurara or dead finish (Acacia tetragonophylla) and dune wattle or umbrella bush (Acacia ligulata). Hakeas and grevilleas, plants of cooler climes, reach their northern limit on Peron. The two botanical zones overlap in a region of tree heath.

Tree heath is the most diverse and complex plant community in Shark Bay. It occurs nowhere else in Western Australia and was a factor in Shark Bay being declared a World Heritage Area.

It occurs in the overlap between the South West and the Eremaean botanical provinces on the southern parts of Nanga and Tamala pastoral lease down to the inland section of Zuytdorp Nature Reserve. It can be seen on the road to Useless Loop, about 25 km from the Shark Bay Road turnoff.

About half of the flowering plant species endemic to Shark Bay are found in this plant community. They include species valuable for understanding how species adapt to different environments and the factors which limit plant distribution and abundance.

Tree heath features scattered trees no more than 6m high. It includes one-sided bottlebrush and dune wattle interspersed with species of Eucalyptus, Lamarchea and Eremaea. The understorey features Hakea, Calytrix, Baeckea, Scholtzia, Pityrodia and Melaleuca, plus numerous herbs and grasses. Among them are unusually large forms of shrubs, a phenomenon some botanists have called ‘gigantism’. Heath species such as Ashby’s banksia (Banksia ashbyi) and Shark Bay grevillea (Grevillea rogersoniana) have exceptionally large specimens in Shark Bay at the northern limits of their ranges.

A large number of plants are restricted, or almost restricted, to the tree heath community:

- Beard’s mallee (Eucalyptus beardiana), an endangered species

- Shark Bay grevillea (Grevillea rogersoniana), a priority species

- Acacia drepanophylla, a priority species

- The herb Macarthuria intricata, a priority species

- Shark Bay featherflower (Verticordia cooloomia), a priority species

- Shark Bay mallee (Eucalyptus roycei)

- Prickly woollybush (Adenanthos acanthophyllus)

- Hakea stenophylla

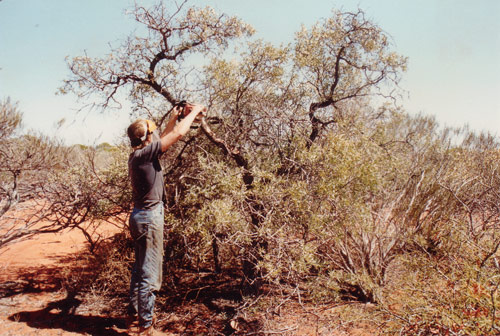

Sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) is best known for aromatic oil and timber used in the production of incense, perfumes and cosmetics. Sandalwood harvesting was one of the first industries in Shark Bay and continued for more than 100 years, mainly for export to south-east Asia. Licences were phased out in the year 2000. Like other members of its family, sandalwood is semi-parasitic and draws most of its nourishment from the roots of surrounding plants.

In most areas sandalwood is harvested by being pulled from the ground, roots and all, but Shark Bay sandalwood is unusual in its ability to coppice, resprout from the stump after being cut down. The new shoots start producing seed after three to four years, ensuring a sustainable harvest. Harvesters working on Nanga pastoral lease in the early 1990s reworked trees that had been cut down during the 1930s.

It is not clear why the Shark Bay sandalwood can resprout but possibilities include the deeper red sand loams encourage a bigger tap root system that can support coppice growth; dead finish (Acacia tetragonophylla) may be a better host plant than those favoured by sandalwood in other areas; or the herbivore defence qualities of the Shark Bay sandalwood’s unusually bitter leaves.

Sandalwood fruit is edible. The golden-brown fruits are 15–20 mm in diameter, have a thin fleshy layer which can be dried and stored, and are delicious when seasoned and roasted. The nuts also produce high quality oil, which some Aboriginal people use as liniment on aching joints. Sandalwood fruits are swallowed whole and dispersed by emus.

Seagrasses are marine plants with the same basic structure as land plants in that they have root systems and produce flowers. They grow in shallow coastal waters with sandy or muddy bottoms and low wave energy – all characteristics of Shark Bay.

Twelve of the world’s 60 species of seagrass are found in Shark Bay, with wireweed (Amphibolis antarctica) and ribbonweed (Posidonia australis) being the two most common.

With about 4000 square kilometres of sea floor colonised by seagrass, the seagrass banks of Shark Bay are the biggest in the world. Many species depend on seagrass, including a large dugong population that moves between different meadows during the year.

Find out more about the seagrass species in Shark Bay below, or on our Fact Sheets & Guides page.

Seagrass Species

Comment

Image

Amphibolis antarctica

The most common species in Shark Bay covering 85% of the seagrass area. Grows from the low tide mark to as deep as 13 metres. Lives in a variety of sediment types. Can be very dense forming 300 – 500 shoots per metre.

Posidonia australis

The second most common species in the bay forming monospecific stands largely in channels. Doesn’t like saline waters – rarely found in water with a salinity above 50 parts per thousand. Only has about half the production rate of Amphibolis antarctica.

Halodule uninervis

Apart from the 2 species above it is the only other species in the bay to form monospecific stands eg at mouth of Wooramel delta, an important summer feeding ground for dugongs. Rhizome of this species is rich in starches. Can be found at high salinities of 62 parts per thousand but in low numbers. Grows rapidly.

Cymodocea angustata

Wide leaved tropical species found no further south than Shark Bay. Endemic to the northern section of the Western Australian coastline and common in Shark Bay.

Cymodocea serrulata

Tropical species with strap like leaves 5 to 9mm wide. Only found in small numbers in Shark Bay.

Halophila decipiens

Has small translucent oval leaves. Found in low densities in Shark Bay.

Halophila ovalis

Narrow leaved species. Can grow on the intertidal flats in sparse mixed stands with Halodule uninervis and Halophila minor. These stands are the preferred grazing area for dugongs. Grows rapidly.

Halophila minor

Narrow leaved species. Mixed stands with H. ovalis and Halodule uninervis are preferred dugong food source.

Halophila spinulosa

Below depths of about 8 metres forms very dense stands of up to 800 shoots per square metre.

Posidonia coriacea

A southern Australian endemic that grows with a clumping habit in areas of relatively high wave energy. Not common in Shark Bay.

Syringodium isoetifolium

Wide leaved species found in small numbers in the bay. A tropical species found no further south. Grows in small areas of high productivity with a number of other species creating a food source for dugongs.

At least 53 plant species are endemic to the Shark Bay region and their restricted range means that some are quite rare. Two are on the national threatened species list, the endangered dragon orchid (Caladenia barbarella) and Beard’s mallee (Eucalyptus beardiana).

More than 56 species in the Shark Bay World Heritage Area are ‘priority’ species. These are species known from only a few collections or a few sites and further study is required to determine their conservation status. There are five priority categories:

- Priority 1, 2 and 3 species – ranked in order of urgency for study and evaluation of their conservation status. There are 10 Priority 1, 20 Priority 2 and 20 Priority 3 species in the Shark Bay World Heritage Area. These include the endemic Acacia drepanophylla, Grevillea rogersoniana, Macarthuria intricata, Physopsis chrysophylla and Verticordia cooloomia. Some of these priority species occur in Shark Bay’s unique tree heath.

- Priority 4 species – adequately known and rare but not threatened. They require monitoring every 5–10 years to check their status. There are six Priority 4 species in Shark Bay, including Jacksonia dendrospinosa.

- Priority 5 species are not threatened but depend on specific conservation programs. If these programs were to end, the species would become threatened within five years. No species in Shark Bay has Priority 5 listing.